The Zambezi valley was sweltering hot. In the thick Jesse bush it was difficult to breathe. The air seemed thick, and each breath seared the lungs as if a blast furnace was blowing directly into your face. Every plant seemed to have a thorn attached, and the sickle thorns grew so prolifically that you could not move a pace without being snagged and held tight. Then you had to slowly disengage the thorns one by one, or the effort would only result in the snag binding tighter and the thorns would penetrate your clothing and start to embed themselves in your flesh.

What made matters worse was the presence of swarms of Mopani flies forming a cloud around your head, crawling into your ears and up your nose, sucking at the corners of your eyes seeking all the available moisture. As soon as you wiped them from the eyes, the ones that were killed let out a fluid which stung the eyes and made them water some more, attracting more flies, and the whole agonizing process started all over again. You dare not slap them because then the Buffalo herd you were tracking would be instantly alerted and would take off through the bush as if the thorns did not exist. So all you could do was to wipe them away gently and just grin and bear their annoying presence.

Edward, my black hunting companion, and I were on a narrow elephant footpath winding our way through the Jesse bush on the trail of a small herd of Cape Buffalo numbering about sixteen grown individuals and a few calves. I was then about fifteen years old, and although I had shot a big Kudu bull with the new, to me, rifle that I had acquired from our family friend, but I had never before hunted the dangerous Cape buffalo.

Edward was a bush wise black man, but even he too had never encountered these formidable animals, and could only relate what the older men in his tribe had to say about these beasts while they sat and talked around the camp fires.

Here we were, in probably the most dangerous terrain you could think to enter, actually on the spoor of a small herd of one of the most lethal animals on the entire planet. We had come across the herd in an open glade where they had been grazing on the sour grass. The sun was about at eight o’clock, and it was already burning on one’s back as if the khaki shirt did not exist. Excitedly we watched the small herd, squatting on our haunches. They were about two hundred paces from us, and we knew that they were too far for me to attempt a shot. All the hunters who claimed to be authorities on these animals told that one should stalk up to at least twenty paces before firing, and then the hunter must be very careful to select the right place on the beast’s body to aim at. I can remember the consensus being that the neck shot just below the curve of the great horn was best, and if the animal was broad side on and a neck shot was dicey, then a heart shot on the shoulder was next best. A brain shot aimed on the point of the nose was an instant killer in a frontal position, or if you were not too sure of striking the nose squarely, then a shot into the depression at the base of the neck was sure to penetrate the heart. Quite easily done if you know how, or so I thought.

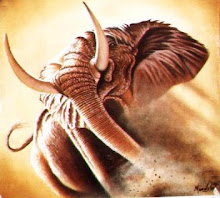

Even at this distance they looked frighteningly large and fierce. A great big bull stood a little apart from the herd, caked in dried mud, and lifting his massive set of horns, he sniffed the air in our direction; nose outstretched and lip curling back. The sight of him made me feel weak at the knees, and a feeling arose in the pit of my stomach making me feel as if I had to attend to an urgent call of nature.

It would have been so easy to just call the hunt off, and go back home, but Edward had faith in my ability to use the white man’s gun to bring down the most dangerous game in Africa, and it did not matter that I had never before confronted these animals let alone knew how to hunt them! And how exactly had I gotten myself into this predicament? What was it that brought me to this inhospitable valley so full of dangers and frighteningly hostile creatures?

Our farm was situated about twenty miles as the crow flies from the escarpment at the edge of the mighty Zambezi river, and where the valley starts was about thirty miles from the river itself. I had seen the river, having crossed it from Southern Rhodesia into Northern Rhodesia over the Chirundu Bridge. At the bridge it was a beautiful green black fast flowing river, and we used to make a stop there just to take in the magnificence of the scene. Sometimes there would be native women, mainly of the Tonga tribe, fishing for Bream (Tilapia) along the banks, and we would buy fish from them which we would cook for breakfast when we arrived back at the farm about one hundred miles away, east past the capital city of Lusaka.

Edward was a piece time worker who stayed with a family member in my father’s employ, and sometimes helped to harvest crops as the need arose, and as there was ample leisure time he would accompany me on hunting excursions on the farm itself. He was a short powerfully built man with the torso of a wrestler, and short bandy legs. His back rippled with muscles as a result of strenuous work with the hoe and axe. We had struck up a friendship, as his passion coincided with mine, which was roaming the bush and hunting in it.

Together we had accounted for a number of large bush pig, some duikers, and numerous guinea fowl which we hunted using our dogs. He could walk all day and never seemed to tire, at first I was hard pressed to keep up with him, and he would not slow down or concede that I needed a rest, but as my level of fitness increased, it was not long before I was setting the pace, and he had to move to keep pace with me. Of course, I always made sure that he was carrying the heavier load, but he never seemed to catch on, and neither did I inform him of the fact. Edward was also one of the minor sons of the chief, living at the confluence of the Zambezi and Kafue rivers, named Chiawa.

After I had acquired the 8x60 Mauser rifle, and had dropped a young Kudu bull of about three years old with it, he told me that he knew of a territory where the game was plentiful and where we could hunt whatever we chose without the government’s consent because it all belonged to his father the chief. If I wanted to accompany him to these happy hunting grounds, I should supply him with some gifts that he could take back to his father, and if I would write out a letter of permission to hunt, then he would get the old man to put his official seal to it, and we would have the best hunting area in Africa at our sole disposal. Dictated more by the folly of youth, an over supply of enthusiasm and the possession of a superb rifle with plenty ammunition, I consented, feeling that I had hit the supreme jackpot. We arranged that when the next school holidays came around, I would return with the gifts, and he would go back home for a visit and return with the written permission.

On a trip into town I drew thirty Pounds (a king’s ransom) out of my Post Office savings account, and purchased a bottle of Limousin (cheap) brandy, a new briar pipe, some pipe tobacco, a new folding knife, a small hand axe and two Waverly rugs. This lot cost me the Princely sum of eighteen pounds three shillings and nine pence. The rugs were the most expensive items, but I resolved that too soon I would extract their full value from the bush to which the old chief would grant me carte blanche.

Edward set off with his uncle’s bicycle, the bundle of gifts strapped to the carrier in an old cardboard box, and as he disappeared over the hill down the track to the Zambezi, I was convinced that I was casting my bread on the waters, and would see returns of at least one thousand fold. I went back to school, and could hardly wait for the next holidays to come round. It felt like an age before they did, and one day, there was my stepfather’s truck to collect me for the long awaited break.

The first thing I asked him was, “Has Edward arrived back?” “Yes,” he answered, “he has been pestering me for days about when I will be picking you up. What mischief are you two planning to get up to this time?”

My mumbled reply was very non informative and softly spoken hoping that the old man would let it pass without further explanation. He did, and with relief I sat quietly the whole way to the farm, and while he was off loading the supplies purchased in town I took off to the house where I greeted my mother, and deposited my suitcase in my room.

As soon as it was safe, I hared off to the worker’s compound where I encountered Edward sitting in the shade of the big Pundu tree carving some axe handles which he sold to make extra cash. As he saw me, he entered his hut and emerged with the note in his hand. There was the chief’s mark, a wavy cross, but underneath was a waxed official seal. We had permission, and now nothing could stop us from harvesting as much game as we wanted. My thoughts went back to books I had read about the exploits of men like Karamojo Bell, Frederic Courtney Selous and other famous African hunters. I was due to join their ranks, and many pleasurable days awaited me in this wide and wonderful land.

We started to assemble our gear. I had purchased two ex army rucksacks, second hand, a new sleeping bag, a pair of vellies, the traditional velskoen of the Boer Trekkers, kerosene lighter, and two cooking pots, one for maize meal pap, and one for the meat relish we would eat with it. Then we had an enamel mug each, and a small aluminum kettle to boil water in for coffee. A small tarpaulin, filched from my stepfathers store, and for use as a ground sheet for me to sleep on rounded off the equipment list. All the soft goods were wrapped in the tarp, and some provisions such as coffee, a few tins of corned beef, a hand full of rice, three small tins of peaches and two tins of condensed milk were stowed into the rucksacks. In mine I had the ammunition, sixty rounds in all, the folding knife, some fish hooks and a roll of fishing line( in case we made it to the river ),some spare socks, a spare shirt and shorts, and the pull through and cleaning kit for the rifle. I also had some mutton cloth to use as a dish towel.

Loaded with our gear and twenty pounds maize meal each plus five pounds coarse salt, we set off for the valley. I had convinced my mother that we were to hunt in the Manica tribal trust lands adjacent to our farm, and that we would be back within a week’s time.

We set off early in the morning at a brisk pace for the valley, and the first night slept in the escarpment right on the edge of the descent into the great Zambezi valley. Making camp we soon had a fire crackling merrily and some food on the boil. I spread my blankets, and after eating went straight to sleep, the chirrup of a nightjar in my ears. Far away a hyena let out a mournful howl, and was answered by another equally as far away. Soon I was fast asleep, and before I knew it I awoke with Edward stirring up the fire for coffee. As soon as it was light enough we were down the mountain side.

The mountain was called Mfundis, because it taught every motor vehicle that you needed four wheel drive to get down or up, and the cooling system must be good or the vehicle would not get more than halfway. Believe me; the cooling systems in those days were always prone to malfunction .But we were on foot, and we literally scrambled down the steep side. I was so keen to get at the masses of wild life that I never even gave a thought to carrying back up everything that we shot!

By mid afternoon we were well inside the territory, and after crossing a small stream still flowing as a result of a good rainy season, we found some tall trees on its bank, and set up camp. Both collected a pile of fire wood, mostly mopani wood which makes wonderful coals to cook on, and can burn all night. That night we sat around the fire and discussed strategy for the following day.

So it was that the next morning we came across the small herd of Buff grazing in the open glade. There was no way that we could approach them without being detected, and while we were sitting there, the old bull shook his gargantuan head and moved leisurely off into the thicker scrub. The rest of the herd followed.

This was our cue, we stalked behind them, but they did not stop, and soon they took an elephant footpath which wound deeper into the thick Jesse bush. I had heard that as soon as the sun starts to warm up, these animals will head into thick cover to lie down, and it would have been prudent to leave them alone. The adrenalin was pumping too much, and we could hear the soft bleating of the calves, and were sure that we would come upon them at any minute. The bush became thicker as we progressed, and soon we were so deep in that we could not see more that a few paces ahead.

The sickle thorn was so tangled that had we tried to get off the elephant path it would have been like walking into a spiny wall. After some time, I don’t remember how long, Edward stopped sank to his haunches and pointed ahead.

There at about fifteen paces stood a large black shape. We could see that it was the general shape of a buffalo, standing broadside on, but we could not make out his front from his backside; a shot to the shoulder would be fine, but if what I was aiming at was the rear end, then it would be a disaster. After about a minute scrutinizing the beast, he moved his ears slightly, and the light filtering through the leaves glinted on his horn, Ah! He was facing to our left, and I could see a clear shoulder shot.

Now the 8x60 is not considered the ideal big game rifle, but it was all I had, and I had full confidence that it would do the job. I took careful aim, and slowly squeezed the trigger while taking dead rest against the stem of a sapling. The shot rang out, and I could faintly detect the puff of dust as the bullet stuck home, perfect shot! The buff should have collapsed right there, but at that moment all I could hear was the crashing and breaking of branches as the herd took fright and scattered, and oh cripes, here was a behemoth careering straight for us! Edward reacted in a split second and took off down the path we had come up, and instinctively I reloaded while watching the black body the size of a freight train,(or so it seemed) come crashing through the bush as if he were on an open highway.

Try as I may, I could not get a bead on his head as the foresight wavered too much, and the buff came galloping over the obstacles in his path, his head moving up and down so that there was no way I could let off another shot. He had obviously not seen us, and ran in our direction after the fright from the mortal shot.

I was afraid that he had seen Edward run and as I had slipped behind the thin sapling, I was out of his direct path. He came thundering past so close that I could have reached out with the rifle barrel and touched him. I was convinced that Edward was a dead duck. I hurriedly stepped out into the elephant path behind the running buff. Raising the rifle to my shoulder, I sighted on his behind, “maybe I could break a hind leg,” flashed through my mind, but before I could squeeze the trigger the bull vanished from my line of sight, and ploughed into the ground in a cloud of dust. Out of the dust I heard a mournful bellow. The bull was dead.

The full jacketed bullet had penetrated his heart, but he still had enough life to get past the spot where we had been firing from, and had he been watching us, and came at a full charge, I shudder to think what would have happened. It took me quite a few minutes to coax Edward out from the Jesse bush which he had gone through like the wind. He eventually came out without one single scratch on him.

Or next problem was to get the ton of meat back to camp, work it into biltong strips dry them and get them over Mfundis to where we could pick them up with the old man’s small tractor and trailer. We worked for the rest of the day to carry the meat piecemeal to the camp, and two days to cut up and salt and then hang the strips to dry. Four times we climbed the mountain path to get the meat and the gear up to where we could collect it, and even then it was not done. I had to leave Edward to complete it while I had to go for the tractor.

Another plan had to be made to get all the hunted carcasses over that torturous obstacle of a mountain, but that is a story for another time.